How sharing notes could be best practices in open peer review

When I was in middle school, I remember checking out a book from the YA section, opening the cover eager to start reading it to find something truly horrifying: the word

“HI”

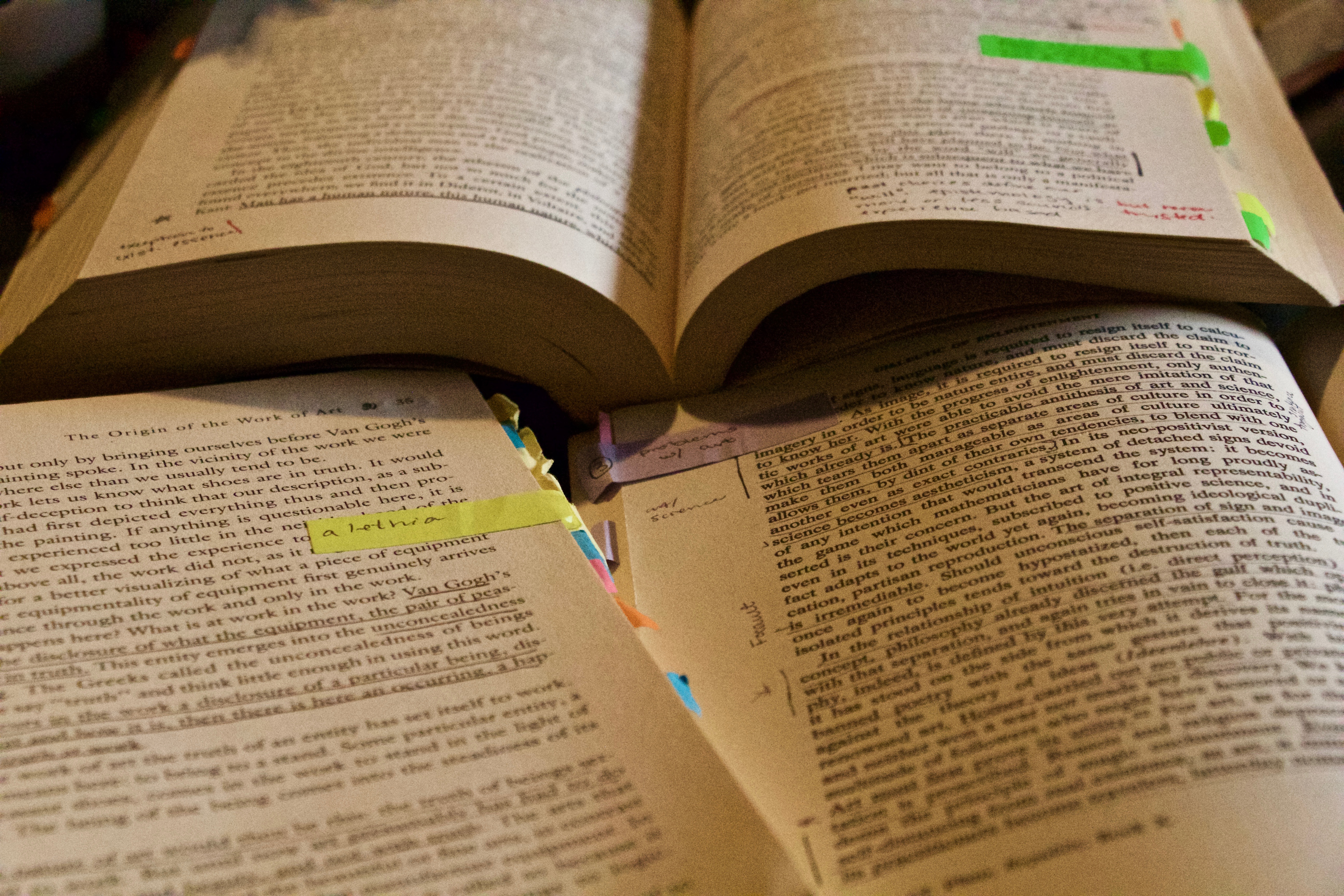

etched onto the title page in bright pink gel ink. The whole while reading it, I kept thinking about the illegal greeting, flipping back to it every so often in frustration; who would dare write in a library book?! By the time I finished the book, however, I had grown accustomed to it and instead of tattling on the unknown writer, I engaged with them, writing a tiny “hi” in a number 2 pencil before sliding it into the returned book box.Since then, now having bought many used books, the concept of highlighted or written-in books has almost become second nature and often exciting, provided the highlights aren’t so frequent the whole page is a neon orange, and there’s enough room for me to write in it too. Yes, I have become my middle school nightmare: someone who writes in books.

As a graduate student researcher, I basically write on any text (digitally or printed), most frequently journal articles. Really digging into the text and the accompanying figures allows one to really get a sense of what the researchers were doing, why, and most importantly, how. Deep dives into papers, for me, involves underlining important parts, highlighting acronyms in green to easily find them again, yellow for important findings or methods, and penned notes for general comments. Each person has their own way of extracting what they need to from a text, making learning a very personal process, but it got me thinking: what if we combined all these scattered annotations, what additional knowledge would we gain from that? Considering a single paper, one that’s been read by lab members, peer reviewers, and journal clubs, we could get a consensus of what’s useful or what’s missing, of good or bad protocols and experimental controls, or of what comes next. Integrating these comments could be extremely useful as a structure for peer review and scholarly community building

Annotation as immersive scholarly engagement

An annotation is an interaction with a text or document. It’s often coupled with “active” or “close” reading, involving the granular act of underlining (or highlighting) pieces of text, drawing glyphed check marks or X’s, and scrawling notes in the margins to analyze or question the contents. Having had this practice for critical reading drilled into my head during high school, I personally find that I’m not really giving a text or book my full attention unless I’m hovering over it with a pen (or a pencil if I have to give it back to the library in two weeks time), ready to underline or annotate at the slightest stimulus. This simple act of engaging enhances readers’ understanding and recall of the text along with making the experience more personal.

Even though these days annotations are mostly private exchanges, this wasn’t always the case. Within the Victorian age, annotated books were passed around to friends and scholars as a social activity (an archaic academic version of the jeans patched and drawn on by the Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants). Before then, Medieval scholars relied on annotation to discuss, critique, and learn from the notes left behind by their predecessors, such notes routinely transcribed with the primary text, typically religious documents. Both of these historical anecdotes either occurred during a time when printed books were expensive or pre-dated the printing press. As such, texts were shared within a community, whereas today books are mass manufactured and each person can have their own copy (especially the Bible, considering every hotel nightstand has one and there are multiple translated versions). Back in the print-era, extra-large margins were provided for scholars to provide commentary, the notes themselves termed marginalia. This tradition continued for the first books printed, and the empty space of margins persisted mostly ever since, extending an invitation for readers to add their own notes.

Perhaps distracting, others’ annotations can provide a more immersive (albeit meta) experience with a text. A particularly striking example being the mystery novel, “S.” “S” is a 2013 novel by Doug Dorst (and conceptualized by film director JJ Abrams) and takes place in the fictional novel Ship of Theseus “by” V.M. Straka, “published” in 1949. The book itself mimics a high school library book, “813.54 STR 1949” stickered at the bottom of the spine, and describes the story of an amnesiac on a strange journey to discover himself, on the tropical shores of the Carribbean. A second (and arguably more interesting) storyline takes place in the margins, the mystery unfolding in the notes between the readers. Without meeting, graduate student Eric and college senior Jen trade the library’s copy back and forth, using the buffered space around the text to solve the mystery of Straka’s identity before Eric’s professor. These marginalia are not always chronological with different pen colors and styles, and are another enigma for the reader to solve along with providing more context to the mystery. Hands down, this is one of the most immersive novels I have read since it invites the reader to investigate the puzzle pieces and solve clues for themselves.

These extra details and reactions in the margins open insights into the story and bring a human touch to a text all about identity. In a world filled with e-mails and digital content, the pleasure that one gets from handling post cards and deciphering handwriting is downright nostalgic and intimate. Perhaps intimacy and the feeling that you’re spying on the original note-writer isn’t the feeling to emulate in a research or scholarly sense, but the concept of having a living, breathing, interactable document brings the text to new life and immerses the reader into the larger community. That handwritten note invites other humans to interact with their comments and their line of thinking in an intimate person-to-person manner.

Bringing comments to the text

Today, discourse regarding academic texts seem to occur external to the text: essay responses, the elegant and dramatic take-downs printed in the following edition of the journal; a pile of 30 critical analyses written by a tenth grade English class; a forward of a book written decades later in a new edition by someone giving greater context. Increasingly, there are more discussions in online groups be they within a publication’s comment section, a question-answering platform (Stack Exchange, Research Gate), and even on social media platforms (Goodreads, Twitter). The internet allows for, indeed encourages, the cultivation of these otherwise private discussions between the reader and the text. Thinking of the comments section on a blog or video, we see how a community can come together to share, critique, and celebrate a particular content.

These “annotations,” while useful, exist separate from, though hopefully linked to, the original content itself. The same is true for traditional review of content as well, be it an editor’s comments about a book submission or scientific peer reviewers on a new study submitted to a journal publication. In this digital age, annotation, especially how it’s typically thought of, is much harder. It’s difficult to write (by hand) in an e-book comfortably, and as such they lack the type of engagement that I’ve personally found to be the only way to engage with texts, scholarly or otherwise. But even typing in responses can be clunky on some platforms, and writing out notes instead of typing them has been shown to improve comprehension.

Even so, platforms increasingly allow for annotations anywhere on the web, in-line and along-side the original content as opposed to a couple of scrolls to the bottom of the page (like hypothes.is, eLife, Medium). As such, digital platforms have the ability to provide much more content and context to a particular text where a physical book margin is limited by space and unable to hyperlink to other sources. Digital annotations could be like bringing all the opinions disclosed within copies of books across the world into a single copy (available to be viewed or collapsed to avoid being overwhelmed, ideally). Such web-based annotations would provide a mechanism for massively and easily sharing responses to a text with other readers right inside the text itself, giving a home to the sharing spirit of Victorian and Medieval scholarly communication.

How annotations and open peer review can be used as an educational tool

Many class instructors share their class notes on a course website, but even still you might ask your friend for the notes if you happened to miss the lecture. The content written down, while important, isn’t everything and typically does not highlight key ideas, provide an alternative explanation the lecturer might have said, or transcribe any questions or debates held during the class. Similarly, a protocol or methods section, perhaps detailed, may not have all the tricks or troubleshooting strategies transcribed. In this context, annotations could provide extra information that would serve as an educational platform, particularly with regards to peer review and methodology.

Peer review

As you write a manuscript about your research, be it in Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or Overleaf, comments from your advisor, collaborators, and peers exist in the digital margins of the text. Such comments can additionally be responded to, allowing for a digital dialogue within the section being discussed. Once you submit your article to the publisher, however, the way you get reviews back is a document that stands apart from the original text.

Making such reviews open, regardless of if they are within the “comment section” or in-line with the text, provides an educational tool for academics. Looking at the peer review summaries from eLife or F1000 reviewers, researchers learn the structure of a review but more importantly what to look for in a study – the controls, the logic, the methodological flaws. Additionally, getting the chance to read such reviews opens doors to academic processes traditionally hidden, where training is sparse. To avoid having the “final draft” look like a massacre from the rounds of edits, sharing a traditional peer review in-line online might require some clever development like version control. This would allow for readers to go back and see what issues the original submission had, how the authors addressed the comments, and made the required changes before official publication (where that peer review process can be as open as the journal wants). These comments made available and linked to the particular sections they refer to would simplify and clarify issues raised and identified in the peer review process as well. (PS the publication platform PubPub lets you do all of these things!)

Once the article is published, that annotation by the community should still occur through a similar annotation process. This “post-publication” peer review extends the duration of the conversation on the final product of peer review. Strengths and weaknesses of a publication within a post-publication review can happen in real-time and clarification regarding implications are immediate. Additionally, it offers opportunities for corrections – perhaps adding in a citation or pointing to a more recent study with an updated model. Most importantly, it invites anyone to contribute to the process, providing a “social evaluation” platform much like product reviews on Amazon. Where the journal has already given a seal of approval for publication, the community response can be a lot different (as now demonstrated via citations). This type of open commentary provides an honest consensus regarding particular studies and hints at what different communities find valuable, something that’s not always taught or even teachable.

Method section

Along with being an educational tool for scholarly practice, having open annotations for research methods would help improve and troubleshoot protocols. To take another example from modern literature, the used potions text-book that Harry Potter is given during his 6th year at Hogwarts contains tips and tricks that help him excel in the class (spoiler alert). “The [Half-Blood] Prince had proved a much more effective teacher than Snape so far…” Harry thinks regarding the notebook, ironically unaware that the annotations were written by Severus himself. Initially annoyed by the scribbles that made it difficult to read the original text (much like “S”), whenever Harry tries the methods scrawled between the lines and in the margins, he achieved better results – even better than Hermione.

Though Harry eventually is found out to have “cheated” his way through his wizard exam prep by using a note-riddled book, such annotations made to method sections within any other context ought to be made readily available, easily exploitable by researchers and readers alike. Some journals like Cell Press and Nature are including sections in their journals that allow for something similar to a form of peer reviewed journal articles that are entirely about method development. Similarly, Nature also has a platform for researchers to share their protocols, presented in a recipe-style format that provides step-by-step descriptions that any one can take to the lab and apply the methods right away (in traditionally peer-reviewed or community-reviewed formats).

Especially within science, where trouble-shooting complicated experiments is part of one’s training, not having to reinvent the wheel saves a lot of time and frustration. That said, even protocols within a single lab are constantly evolving as members discover more tips and tricks, these updates rarely transferred over to the official PDF on the archives until said member has to graduate. Having immediate access to the best method that has consensus might also reduce the reproducibility crisis within science too, where protocols are explicitly detailed and encountered issues are explained.

Community building in annotations

Beyond the chicken-scratch annotations on an article you’re reading helping your comprehension, integrating them with other commentary scattered across the world would serve as community-based peer review. Through consensus, the highlights and main takeaways of a study or field are easily identifiable, the methods section improved, sticky or confusing sections explained, questions answered, etc. Such community commentary already is embedded within research via conferences, meetings, and paper rebuttals, so integrating them into publications themselves (the currency of scholarship) is practical while building additional layers of meaning.

With research as discourse, these annotations could upstage the main text, with philosopher Derrida proclaiming “if I want to be sure that my reply or my attack will be read and not passed by, indeed read even before the main text, I put it into a footnote.” Certainly this is not to say that marginalia will overcome publication content, nor will it outcompete meetings or conferences, but that annotations themselves are a powerful tool that could be embraced by scholarly communities to improve their fields of research as they once were, if not just to highlight an important idea.

With these types of comments, especially coupled with a commenter-identifier platform like OrcID, readers (and the authors) can find out what their community thinks of a particular work as it stands, from established members to learning undergraduates or high school students. Having this open community, the works themselves can be assessed for what they are and how they relate to the body of existing and growing knowledge, all together improving how scholarly communication and learning happen.

Our culture, while increasingly digitized, strives for shared experiences and immersions. Marginalia feeds that desire by giving readers’ observation more currency and impact in a given body of work. It opens doors to, from, and between scholarly communities by forming “ivory bridges,” structures that invite various disciplines and the general public to the conversation. These demarcations pressed into the pages of scholarly texts, when combined help the annotator along with any future reader of such annotation and the community at large.

These insights – these digital conversations – all come down to small seemingly insignificant notes, that one gel-penned greeting in the cover or that aha! moment underlining a detail in the supplemental information section. With new functionality, publishing platforms can re-support the functionality of marginalia that we had when content was print-exclusive. Opening space for dialogue in scholarly communities, annotations can move from the side lines and take center stage of academic communications for the better (and in ways that don’t destroy library books).

If you liked this, check out a mirrored version on PubPub – there you can make comments and interact with the text!

Working towards getting her Ph.D. in Chemical Biology at the University of Michigan, Sarah studies the molecular roads of the cell using microscopes. Outside of research, she is active in science communication by writing for her blog Annotated Science, being a fellow with MIT Press’ Knowledge Futures Group, editing and serving as Manager for MiSciWriters, and having chaired the inaugural ComSciCon-Michigan. Sarah also loves to bake bread, take photos, make playlists, and drink lots of coffee. Connect with her on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Leave a Reply