This year, I’ve been hosting podcasts — a shocking thing to any of you who know that I hate public speaking and conversations with strangers — with the New Books Network. Luckily, once I finish their book, the authors no longer feel like strangers since I’ve spent time with their thoughts, their tone, their ideas for at least a few weeks. These interviews go up on the NBN website, but I’d like to try my hand at some creative non-fiction essay based on some of my impressions or tangential ideas prompted by the book. As such, these will not be a formal book review. It feels appropriate, given my odd curiosity for black holes despite being a biochemist by training, to start this experimental series with Heino Falcke’s Light in the Darkness (the podcast interview will be linked here once it’s produced and published).

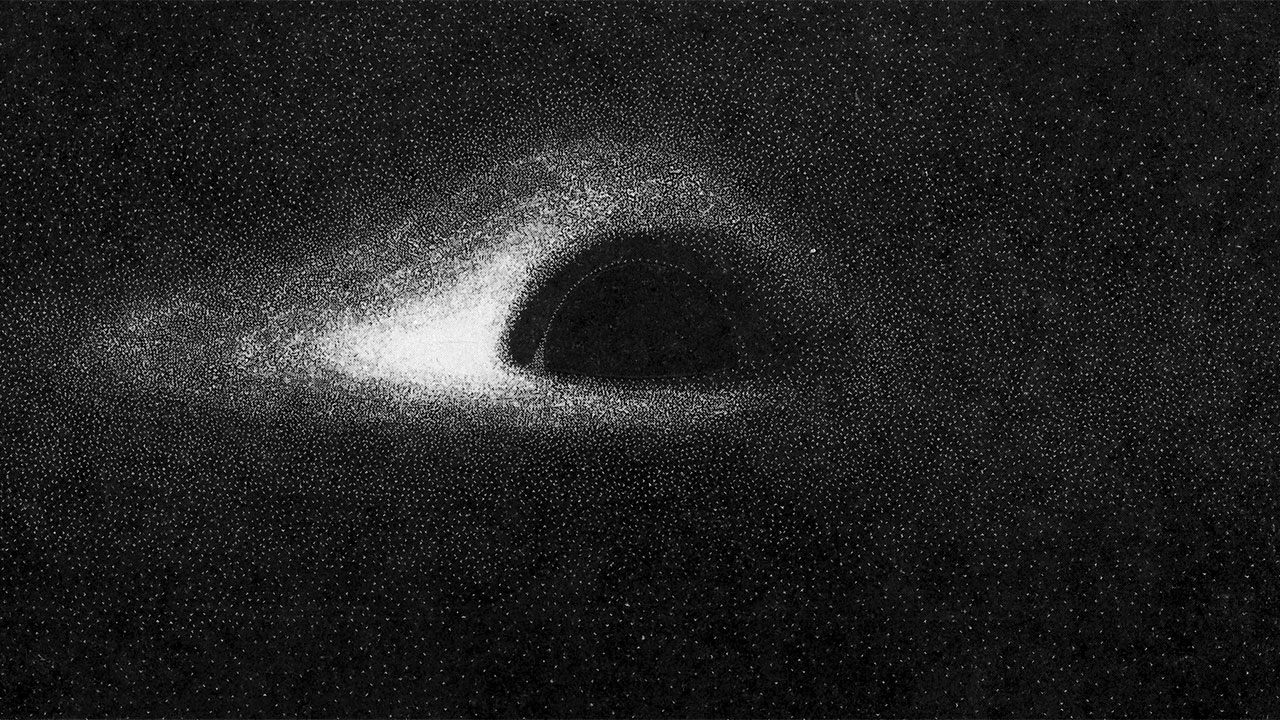

Book description: On April 10, 2019, Heino Falcke presented the first image ever captured of a black hole at an international press conference — a turning point int astronomy that Science magazine called the scientific breakthrough of the year. That photo was captured with the unthinkable commitment of an intercontinental team of astronomers who transformed the world into a global telescope. While this image achieved Falcke’s goal in making a lack hole “visible” for the first time, he recognizes that the photo itself asks more questions for humanity than it answers. Light in the Darkness takes us on Falcke’s extraordinary journey to the darkest corners of the universe. From the first humans looking up at the night sky to modern astrophysics, from the study of black holes to the still-unsolved mysteries of the universe, Falcke asks, in even the greatest triumphs of science, is there room for doubts, faith, and a God?

Metaphorically speaking

One of the things that impressed me about this book is it’s use of analogies. As someone who fancies themselves a science communicator with not a small amount of physics background, I still found myself impressed and blown away at the set up and pay off of the examples Falke uses in this book.

Let’s say I’m in the ocean on a surfboard. There’s a stiff wind blowing toward land and I’m paddling out perpendicular to the line of surf… If I change directions and surf with the wind and waves, I’m just as fast as the waves. Relative to my surfboard. The speed of the waves is small; relative to the shear, the speed of the waves is very high. The same thing holds true for sound waves.

In the ocean of spacetime, the event horizon is the coast. The storm is the blackhole; instead of wind energy there is gravitational energy.

Certainly, Falke is not the first to use metaphor in science communication — there’s been a long history, especially in physics, of leaning on analogies and similes to explain difficult ideas. We can look no further than the Stephen Hawking’s “Brief History of Time,” to find other brilliant examples of the use of metaphor and visualization.

The event horizon, the boundary of the region of space-time from which it is not possible to escape, acts like a one-way membrane around the black holes: objects, such as unwary astronauts, can fall through the event through the event horizon into the black hole, but nothing can ever get out of the black hole through the event horizon… One could well say of the event horizon what the poet Dante said of the entrance to Hell: “All hope abandon, ye who enter here.”

Stephen Hawing, A Brief History of Time

Beyond science communication, metaphors are common in language, especially literature, and are lived out in our lives. They’re useful for understanding complex ideas in simple terms. Analogies and similes give tangibility to abstract concepts. They make the realm of ideas a bit easier to play around with and visualize. Once X is mapped onto Y, X becomes a bit more easy to understand because we know what Y is, and X becomes a thing that we can comprehend through its representation in Y.

Metaphorical thinking — our instinct not just for describing but for comprehending one thing in terms of another, for equating I with an other — shapes our view of the world, and is essential to how we communicate, learn, discover, and invent.

James Geary, I is an Other

To use a metaphor well means that it represents the intangible sufficiently. It’s not over-romanticizing, it’s not under-appreciating, it’s not over-stating, or under-stating. These are tough balances to strike. When I come across a good one, it is poetic, it’s clever, it’s the porridge that’s “just right.” For myself, I can feel like Wodhouse’s Bertie struggling to figure out precisely the right analogy, stumbling to find the right phrase without the brilliant butler to help get me out of a rut. Settling for the wrong analogy can bring about its own comedy of errors. And even the best metaphors can only go so far before they break down.

For me, this calls into question what metaphors and similes that I’ve bought into in my own life. Which abstract concepts don’t align with their analogies, and at which point they should be considered a concept in their own right without the support of the simile. One such analogy I’ve been fixated on lately is “life as a hike” to such a degree that I use questions like “what’s waiting for me at the top of the mountain?” and “who will (I) be on the other side?” as guiding questions for what I’m doing as I hike up the mountain of life. So far, it’s fit — I can assess and strategize which mountains I’m going up, I can set and change the pace, I can celebrate the views from the top and decide which peak to ascend next — but analogies aren’t perfect. At some point they’ll break down. Or in some cases lose their meaning entirely as language and cultural associations change (here, I’m thinking of George Orwell’s ‘dying metaphors’), though I hope that we don’t destroy our planet to the point of losing mountain ranged topology.

Metaphors should be use to introduce the topic, to initiate thinking, to be able to start conceptualizing the unknown, to make tangible the intangible, make poetic the peculiar. But at some point, the abstraction must become their own objects. Black holes aren’t a coastal storm. Life isn’t a mountain. Metaphors can limit our thinking the same way they can expand it. And perhaps that’s part of the beauty in “Light in the Darkness,” that Falke knows or at least intuits the limits of the metaphors and doesn’t take them too far. He knows when they’re useful and when to ground them back into the reality of the data or more apt, the reality that much is still unknown so we have to rest on metaphors for the time being until there’s more discovered.

Becoming a humble seeker

While the scientific implications of black holes are largely theoretical and still being measured, calculated, and analyzed, the [implications] and the symbol of black holes is palpable in more philosophical and even religious contexts. What is beyond the black hole is unknown, but it’s ever more clear that black holes are at least a portal to that unknown beyond. And such a powerful portal that not even light, the very first thing in the beginning, cannot escape its pull. Literally such entities go beyond physics, indeed a metaphysics. Black holes then are another threshold crossed at the end of our time. On a human scale, biological death is one threshold into the unknown. Perhaps our souls go onto Heaven, maybe Hell, or if dying in battle to Valhalla.

The unknowns of what the great beyond could even be or mean is incomprehensible in an experimental context, its not something that the rationalistic process of scientific experiments could begin to answer. It demands a different, a bigger, framework and highlights the limitations of science. Falke notes this limit:

Science is not an absolute method for explaining everything in and beyond the world, but rather a celebration of human creativity and curiosity.

Especially these days where it’s been made exceptionally clear that scientific recommendations can change rapidly it can seem like a house built on the sand, not something study enough to withstand the force of a black hole, let alone the impetuous doubting and skepticism known to humankind, and not something that can really answer “why are we here?” Or “what is the purpose of or within life?” Science, as it is practiced and thought of today, while an admirable process of trying to understand the world, still at the same time reduces it to measurement. Science aims to solve mysteries, and to have closure, to move on to the latest and greatest problem to solve next. We personally experience that as being merely numbers to social media conglomerates, the human soul just a series of numbers when we know and believe humans to be much much more. Science, despite often being entrenched in academic bureaucracy and hence slowness, still strives to “move fast and break things,” it’s bought into staying hip and trendy to play the grant game, and to have a substantial impact (factors). But you don’t have to be a scientist to understand the frustration of limitations. Indeed, Falke writes that,

there is also a kind of solace to be found in limits, because they frustrate human arrogance and allow us to believe and to hope

and goes on to suggest that,

The time has come, then, for us to stop being over-proud conquerors of worlds and go back to being humble seekers.

I think there’s a common idea that religion is incompatible with science. Or perhaps I think it’s common since I held onto that belief for a long portion of my life. I was raised Catholic, had a falling out with Church and disavowed faith of any kind, and became a scientist. Certainly, this is a reduction of my motivations and only a small part of my life’s trajectory. I wouldn’t say that I became a scientist to reject God, but the identity seemed to suit me at the time: neglecting to look up at the sky or inward in prayer to wonder, and instead examine and study the inner workings of humans via biochemistry, via numbers, via measurable quantities, via what I thought of as knowns, compared to the incomprehensible behaviors of humans in this dark universe. From my estimation, to believe in God while pursuing this rationalistic process seemed paradoxical, impossible even, contradictory especially within the life sciences, a sphere where genetics and evolution are central. Which is also funny to think about given that Gregor Mendel, the geneticist who studied hereditary in pea plants, was a Christian monk. And in an astronomy context, Copernicus of the famous Copernican revolution, suggesting that the Earth rotated around the sun, not the other way around, was also a Christian and was seen as a heretic. While I knew these facts, it took me a while to actually understand them and put them together in my head.

In part, the synthesis of religion with organized curiosity (essentially what science is) came with great help from Christian friends and groups that I came across. In both undergrad and grad school, I felt the vastness of something missing and felt called back to church, and while these efforts haven’t really stuck as habits, I’m still drawn to Sunday mass, towards asking and trying to find peace and meaning in the beyond. And now I can at least see that science can be a way to find God in all things, that Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam can be found with microscopes and telescopes as well as gratitude and prayer.

And if I’m blinded then at least you know I tried looking up and I saw light, yeah we’ll be alright.

Grandview, Sitting on Gold (The Latter)

Even more than science as a way to appreciate His great creations, I’ve come to understand that everything has limitations. That religion cannot answer everything. That science cannot answer everything. That the humanities cannot answer everything. There will always be a gap in knowledge, in understanding, especially when choosing to only focus on a particular genre of knowledge. We need a bigger perspective when we’re trying to tackle questions of meaning and purpose. I’m not sure where those will be found, but I don’t think it’ll be through the scientific method, again, not at least while science focus on reduction. Indeed, Falke echos this sentiment:

Heino Falke, Light in the Darkness

One’s sense of worth is not a physically measurable quantity. It must come from without and be felt within. If someone declares their love for you, this declaration cannot be comprehended with particle accelerators or telescope… [it] is an extremely personal thing.

Something I’m coming to appreciate, too, is that the unknowns are more important than the knowns. We sit at the precipice between order and chaos, as one lobster loving Jordan B Petterson might say, when we’re looking out into that vast unknown and pushing ourselves and our understandings to the limit. It’s jumping into that tempest of the oceanic blackhole and hoping that we come out transformed. As a creature of comfort like most humans, this idea is terrifying. But that doesn’t mean I’m not going to leap off the cliff, or at least dangle my feet over the edge (at least with the comfort that my mountain metaphor still holds).

Leave a Reply