Book description: In 1977 NASA shot a mixtape into outer space, The Golden Record aboard the Voyager spacecraft contained world music and sounds of Earth to represent humanity to any extraterrestrial civilizations. To date, the Golden Record is the only home-made object to have left the solar system. Alien Listening asks the big questions that the Golden Record raises: Can music live up to its reputation as the universal language in communications with the unknown? How do we fit all of human culture into a time capsule that will barrel through space for tens of thousands of years? And last but not least: Do aliens have ears?

Listen to the interview with the authors:

Music is embedded in our culture, and it can communicate beyond particular languages. Language-agnostic communication was the hope of SETI/NASA’s Voyager Mission when they included the Golden Record, a small phonographic record shot off into space. The mixtape itself contains greetings in 55 languages, a collection of Earth sounds, and 90 minutes of music composed of 27-songs. These works, intended to capture humanity serve more as a time capsule of humanity during 1977 nevertheless aimed to be a timeless message to lifeforms beyond Earth.

However, for any alien to listen and see the images on the Golden Record, there are many assumptions made:

- They’ll have to be able to decipher the pictographic instructions

- They’ll have to have the technology to project the images

- They’ll have to have the dexterity to handle the record

- They’ll have to have the correct auditory processing biology/technology to hear the frequencies we’ve recorded the music

As Chua and Rehding note, many animals — more accessible Others we have not been able to communicate with — couldn’t do any of this. “Dolphins and whales, with their lack of feet… and of hands … are veritable aliens on our blue planet. Ironically, given their fins and flippers, one of the most intelligent species on the planet cannot handle the Golden Record.” Moreover, the ocean would create a surround sound underwater experience that they could feel with their jaws, rather than their ears. This undoubtably is not how the record senders intended it to be listened (if records can even be played underwater). Other types of animals, like the cephalopod family, have a limited frequency range rendering most of the music on the record inaudible and like a dog whistle to human ears. These complications, “given the infinite possibilities of hearing latent in the universe,” provides a greater likelihood of disconnection rather than connection with an alien listener. “Miscommunication must be an underlying premise of exomusicology as long as the auditory system of our alien recipient remains the big unknown.”

In some ways, this miscommunication may not matter or may not be a miscommunication at all. Carl Sagan, aware of the possibilities of miscommunication, said “whatever the incomprehensibilities of the Voyager record any alien ship that finds it will have another standard by which to judge us. Each Voyager is itself a message. In their exploratory intent, in the lofty ambition of their objectives, in their utter lack of intent to do harm, and the brilliance of their design and performance, these robots speak eloquently for us.” The message, beyond the culture encapsulated in the record, is that humans explore, that we take risks, that we have some sort of eye and mind for design and patterns, that we want them to find us and try and communicate with them.

This point about miscommunication reminds me of some threads in another work I was reading at the same time, a very complementary one even perhaps: Malcom Gladwell’s “Talking to Strangers.” In this work, Gladwell takes the reader through case studies, conversations between spies or political leaders, and scandals to try and identify assumptions and frameworks that we have when we are talking with people we don’t know, and shares with the following ideas:

- Default to Truth: We assume that people aren’t deceitful until there’s enough reason for us not to believe them. We can have doubts about people or about statements, but people will often believe them until there is enough (and that threshold is different for different people/organizations/institutions) evidence to not listen to certain individuals (or organizations/institutions).

- Transparency: If someone seems confident, we assume they’re telling the truth; if they seem anxious or shifty then we assume they’re lying. In most cases, this is true. But some nervous people in stressful situations get anxious even if they’re telling the truth. Very good liars also will make themselves seem very confident when they’re fabricating a story. Emotional expressions, while we like to think they’re critical to read a person, there’s little correlation between facial expression and truth-telling.

- The truth “is not some hard shiny object that can be extracted if only we dig deep enough and look hard enough. The thing we want to learn about a stranger is fragile. If we read carelessly it will crumple under our feet… [w]e need to accept that the search to understand a stranger has real limits. We will never know the whole truth. We have to be satisfied with something short of that. The right way to talk to strangers is with caution and humility.”

Even though there are patterns in how humans try to understand each other, at the end of the day we never will understand even another person (or entity) completely. We may come to know others sufficiently, enough to be able to tell if they’re truthful or not, but there are real limits in our ability to decipher strangers. And even if there are clues to decipher an Other, “attending to them requires care and attention.” How can we provide this care and attention to aliens when we — we as NASA/SETI/Voyager Mission — haven’t or can’t even seen an alien?

Alongside the assumptions made about how to communicate, there are also assumptions about what the media of communication: music. Music as we humans know it is differentiated as something intentional or otherwise. We hear patterns and tunes in sounds outside of us and are inspired by them. Whale songs — whales communicating to each other, not necessarily singing — are moved enough to create a movement around saving and protecting whales. However, “music is premised on an audition that may or may not be realized. Contact is a fragile and uncertain affair. This is because music’s universal “voice” can be heard only by an other who is always particular and contingent. This could be “unintentional” music (a Bolivian villager attending to a babbling brook to collect songs, for example) or voluntary (such as a Bolivian mother babbling a lullaby to her newborn), but the hearing is always particularized as a transformation of the music, rather than a transmission, bringing the other in relation through difference.”

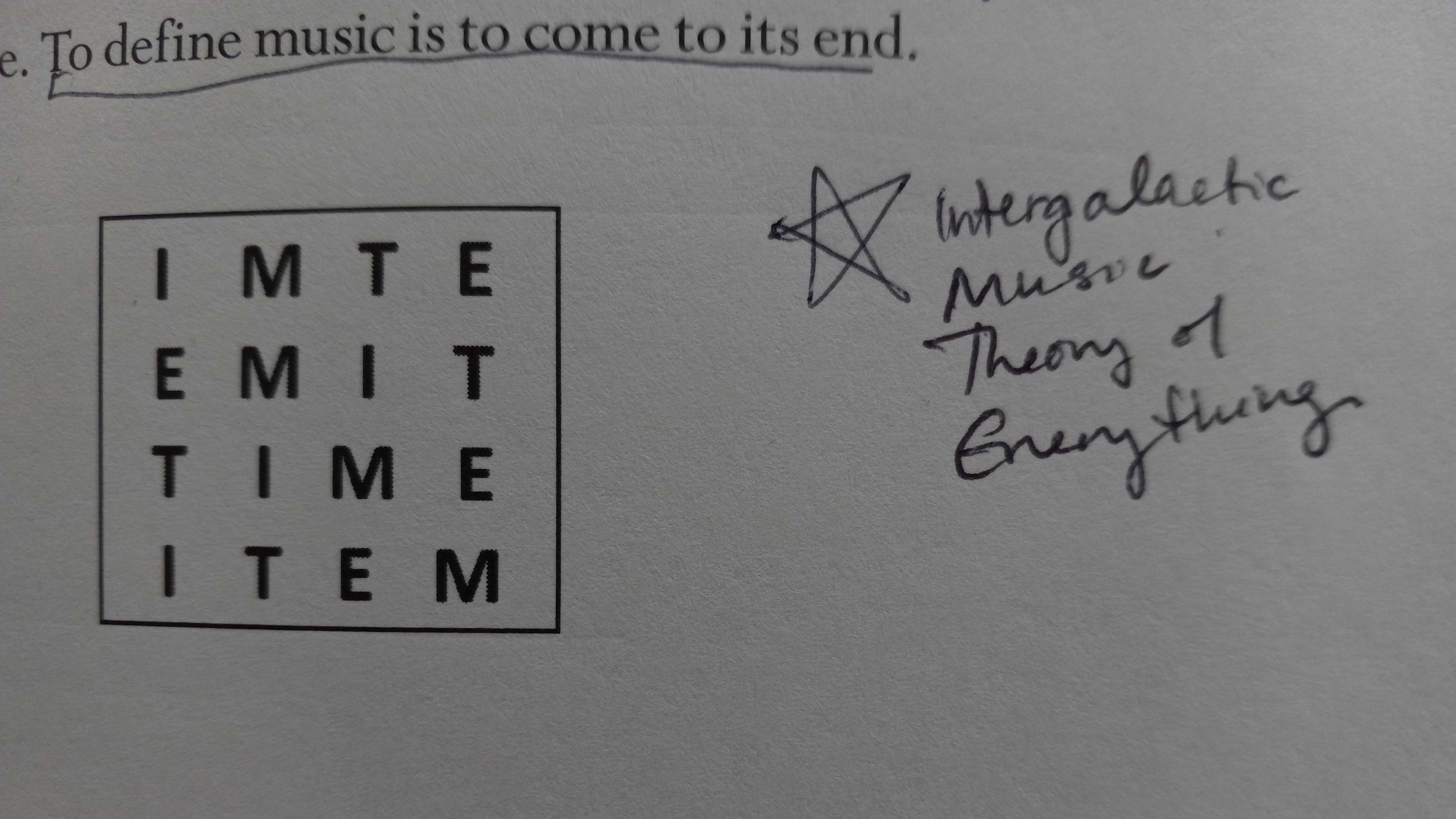

Music — and more broadly the Intergalactic Music Theory of Everything that Chua and Rehding start to define in their work — is much much more than what humans make. It’s much more simple than the rules and guidelines that music theorists construct. The authors reduce it down to repetition: the repeating of sounds and the differences or variations of the sounds as they are repeated is all music is. This simple framework of music open it up to more possibilities, more ways to communicate, more ways to express ourselves through sound and music.

While this work does not so much analyze the cultural significance of music, it is somewhat a treatise to — and frequently notes that — the Golden Record as a labor of love filled with more mysteries than closures. There’s a wide range (though arguably not enough diversity, it is after all a cultural capture of the late 70’s) in the soundtrack, they don’t really go together if you listen straight through. I think if I came across this without any context like an alien will one day, I’d be really confused. Even so, “if our struggling humans prove incapable of solving [the world’s] problems,” speaking of our current climate crisis and the eventual heat death of our solar system, “the golden disc will be Earth’s final testament to the universe.” The strange and eclectic record will likely all that’ll be left of the Earth and humanity one day. Our planet will burn out and be destroyed either by human production or by the inevitable heat death of the universe. As such, it’s important to listen and really hear the songs on it, this record that’s made for aliens but as a reminder to humans to listen to the songs that were made to be listened to for our auditory range, and to be humble at our place in the universe.

In an aphorism, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote how music can teach us something about how to love, and can think of no better conclusion to this piece:

First one has to learn to hear a figure and melody at all, to detect and distinguish it, isolate and delimit it as a separate life. Then it requires some exertion and good will to tolerate it in spite of its strangeness, to be patient with its appearance and expression, a kindhearted about its oddity. Finally there comes a moment when we are used to it, when we wait for it, when we sense that we should miss it if it were missing; and now it continues to compel and enchant us relentlessly until we have become its humble and enraptured loves who desire nothing better from the world than it and only it. But that happens to us not only in music. That is how we have learned to love all things that we now love.

Nietzsche, Gay Science

Leave a Reply